KNIFE GUIDE

In this section you’ll find tips to help you decide what kind of knife to choose, along with answers to frequently asked questions about the materials and the suitability of carbon damascus steel knives for different uses.

What materials do I use

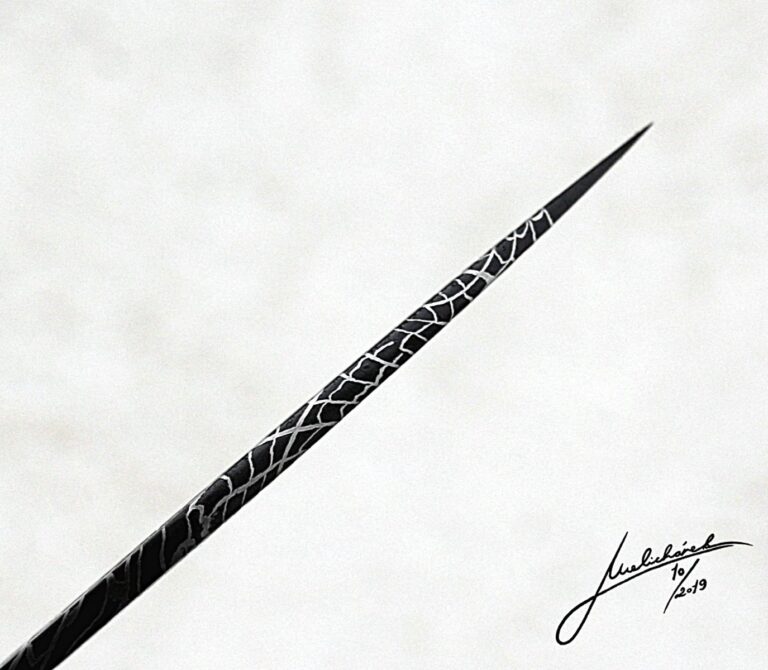

Unlike the jewelry, that you can find in another part of this website, for my knives I work almost exclusively with carbon damascus steel of my own making, combining steels 1.2842 (O2) and Uddeholm 75Ni8 (15N20). I also sometimes use so-called go-mai , which create a bold “lightning strike” pattern. These steels are not stainless. What that means for everyday use of a knife will be explained further on. In the past I also made partially quenched blades with a so-called hamon or blades from stainless steel go-mai. Today I use those materials only occasionally, and focus mainly on more complex carbon damascus knives—especially the ones with twisted and mosaic patterns.

What is damascus steel?

The history of so-called damascus steel reaches far back into the past, and there are several more or less accurate interpretations of what true damascus is supposed to look like. There’s no need to dive into the deeper academic debates carried on among professional knife makers or blacksmiths—for our purposes, a general explanation will do just fine.

Today, the term “damascus” usually refers to layered steel, made through the complex process of forging thin sheets of different types of steel, repeatedly folding them, and forge-welding them in the fire. The resulting material is then further shaped by forging, pressing, twisting, or grinding—depending on the pattern and properties that are desired. The outcome is an endless variety of beautiful patterns, which appear on the finished piece after it is dipped in acid. Since each steel reacts at a different rate, the surface reveals not only visual contrast but also a tangible texture of the damascus pattern.Put simply, damascus steel consists of many “layers” of different steels, firmly

bonded together in the forge into a single piece.

Is damascus steel something better?

I often come across this question, mainly because damascus steel is surrounded by many myths and legends—from tales of unbreakable steel to stories of knives that could supposedly slice other knives into pieces without taking any damage themselves. But is there any truth to it? Does such a thing even exist? And is damascus steel really that good?

There’s a fairly simple answer to this. It’s a kind of golden rule that applies universally and goes like this: “Damascus is not a material, but a technique of forge welding different types of steel together.” Once you understand this, you’ll also have the answer to most of your questions. It’s just like cooking soup: with the right ingredients you can make a rich, delicious broth, but if you just toss bad ingredients together at random, you’ll end up with something inedible. Both are technically soup, but the result will be completely different.

So just because something is labeled as damascus steel doesn’t mean the knife will be of good quality. All it really tells you is that the knife was made using the technique of forge welding different types of steel together. If it’s made from old „tin cans“, you might still see a visible pattern on it, but the quality will be terrible. That’s why you should always ask: what steels was the damascus forged from, under what conditions was it made, whether the material was overheated during forging, how it was heat-treated, and so on.

An established knife maker will give you full information about the materials, and you can rely on a certificate. But just as easily, you can be fooled into buying a “guaranteed quality” damascus knife that claims the right steels and the right heat treatment—yet in reality it may not be true at all. This is especially the case with mass production from certain third countries, which floods the market with knives of very questionable quality. So always be careful! Use your common sense and don’t get tricked.

So is a damascus knife – properly made – better in some way? Well, this is where things start to get a bit more complicated. In the past, yes. In more recent times, partly. And today it’s fair to say that modern steels—whether classic tool steels or advanced powder-metallurgy stainless steels—outperform traditional carbon damascus in many ways. Steels such as modern powder stell Elmax, for example, offer great edge retention, very good toughness, and excellent corrosion resistance.

So why would anyone today want to choose carbon damascus, which needs care, when they could have a higher-performing, maintenance-free knife for less money? The answer is most likely aesthetics, style, and a certain soul that comes from the complex forging process. I like to compare it to a vintage car. Why drive a classic when modern cars are so much more comfortable, better, and faster? A vintage car smokes, rattles, goes slower, and gets hot inside—yet it still has something special. It’s about the feeling you just do not get in a normal car. And of course, driving a vintage makes you look much “cooler”.

Other comparisons could be made as well—for example with shoes or fashion. These things, even though they’re often impractical, people wear simply because they like them and because they express their personality. At the same time, I wouldn’t want my words to sound as if properly made carbon damascus were something inferior. Definitely not! A well-composed and well-processed carbon damascus knife will easily outperform 99% of the knives commonly sold in regular stores!

Steel grades I use

For making damascus steel I’ve been using the combination of steels W.Nr. 1.2842 (O2) and 75Ni8 Uddeholm (15N20) for a very long time. This pairing offers overlapping hardening temperature ranges, which is extremely important—it ensures excellent heat treatment with consistent results, and in my opinion also provides the best possible contrast in damascus. The finished knife, when brought out to its full potential, shows a truly black-and-silver look. I forge only from new steel purchased with a certificate and have not used any recycled steels for many years, since I don’t know their origin. This guarantees a consistent quality output every time.

Tool steel W.Nr. 1.2842, known as O2 in the US and other countries, offers—thanks to its composition of carbon, chromium, and vanadium—excellent cutting performance and good edge retention. The added vanadium, through its carbides, also gives the edge a noticeably more aggressive, sharper “bite.”

The 75Ni8 steel from the Swedish company Uddeholm (US equivalent – 15N20) is a carbon tool steel with excellent toughness while still achieving very good hardness. With about 2% nickel, it also produces a beautiful silver color in the etch. A ratio of 1:6 to 1:10 in favor of the harder “black” steel 1.2842 ensures a good balance of toughness and hardness in the finished damascus. In hardness tests performed on a certified tester, I found no measurable differences between the individual layers.

For certain types of knives—such as kitchen knives—I add the cutting edge either in a san-mai/gomai construction or by welding an extra edge onto the twisted bars. This naturally ensures complete homogeneity of the edge. But even my damascus knives with the pattern running directly into the edge show no significant chipping. Properly matched hardening temperatures provide a consistent edge. Because I’ve been using fluxless welding in a gas forge for years, the steel is perfectly clean, with no enclosed flaws or weld defects. I usually harden my knives to between 58 and 62 HRC,depending on the desired properties of the knife—higher for kitchen and small cutting knives, lower for heavy-duty chopping blades.

Purpose of each knife

The first thing to understand is that every knife has its purpose. You don’t chop logs with a straight razor, and you won’t slice onions with a heavy camp knife. The idea that there’s a single universal knife for everything—one that can never be broken—is completely false and will only lead to disappointment for the user and damage to the knife. Always use a knife only for what it is designed for. When placing an order, we’ll discuss the intended use and purpose of the knife. I’ll suggest the material, blade thickness, and grind geometry so that everything suits its purpose.

Knives for shaving or cutting soft materials

This category includes primarily straight razors and some very thinly ground knives, as well as certain kitchen knives. Permitted use is limited to shaving and/or cutting paper, fabric, cork, and similarly soft materials, or cutting soft foods only

Cutting knives

This category includes most smaller, very sharp pocket knives. You can cut all soft materials such as wood, leather, paper, and so on. Given the knife’s small size, overall slender build, and fine grind, you can also carefully cut harder woods—provided you avoid any prying. This category also includes part of the kitchen knives.

General-purpose knives

With these knives you can handle most routine tasks. You can cut any wood, rope, and similar materials. The knife should withstand light chopping into bone, antler, and the like without damaging the edge, and it should tolerate light prying (be careful with the tip). The mentions of prying and bone-chopping are there to indicate durability—they are not intended uses. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, a knife is always meant for cutting.

Camping and outdoor knives

These knives can handle rougher use, taking into account the materials they’re made from. You can cut as needed, chop branches, and prepare firewood. Normal prying is possible, and the tip can also be used for some light prying. Always keep in mind, though, that it’s still a knife!

Knife for extreme use

A practically indestructible knife — it can tolerate drops, rough treatment, heavy prying and extreme force. In the most extreme situations you can use it as an improvised anchor stuck into rock to hang from. It should also handle cutting through wire and similar abuse

General rules of use

As you can see, every knife is designed for a specific purpose. In other words: “Be reasonable and only use a knife for the tasks it was made for!” Unless stated otherwise, do not chop, throw, or pry with the knives, avoid dropping them, and store them in a dry place. Never wash a knife in a dishwasher! Before first contact with food, wash the blade with water and a small amount of dish soap to remove any remaining mineral oil used for preservation. For ongoing protection against corrosion, use a food-safe oil—camellia oil works very well, but olive or sunflower oil can also be used. You can find more details in the “Maintenance” section.

Handle and sheath materials

For my knives I use a variety of natural and stabilized woods, bone, antler, and other mostly natural materials. When choosing, think about what the knife will be used for. For heavier-duty use it’s wise to consider stabilized wood, which is impregnated with epoxy resin under alternating vacuum and pressure, giving the wood extreme durability. Those who prefer “pure” materials can go with natural wood—but even here there are differences. Some woods are extremely durable even in tough conditions, while others are much more delicate. This should always be kept in mind when making a choice. Of course, I’ll be happy to advise and suggest a suitable wood based on the intended use of the knife.

I also work with other natural materials, especially various antlers and horns, bone, or fossil walrus and mammoth ivory. Most often I use cow and ostrich bone sourced from farms, as well as deer antler and, above all, naturally shed reindeer antler. I never use elephant ivory, “fresh” walrus ivory, or any other natural materials from endangered animals! Nor do I use elephant or walrus ivory even if it comes with so-called “legal documents.”

I know there are places where elephants are used for work and tusks are obtained legally, and that on walrus beaches collections may be carried out by indigenous people or through authorized hunts. But it’s not worth the risk to me. You can put anything on a „certificate“, and a document of legality can be faked with a few clicks in Photoshop. So I reject this outright. I prefer biodiversity to wiping out endangered species for a luxury handle or sheath material. For sheaths I use almost exclusively cow leather in various thicknesses.

I make them to match the knife’s intended use—from simple pouch sheaths to more complex designs with retention straps and decorated damascus buttons. I also dye them to fit the knife’s overall design, and I almost always add wet-tooled lines and motifs.

RUST

A carbon damascus knife requires specific care, and you need to look after it accordingly. These knives are not stainless! Keep the knife dry—ideally with a light coat of oil. Moisture, sweat, and acidic foods accelerate rust. Please read the “Maintenance” section carefully, where I cover this topic in more detail.

Design

I’ll freely admit that the aesthetic and design side of things is one of my main focuses when making knives. In a way, I create artistic and decorative pieces, and I simply enjoy that kind of work. But I’d like to emphasize that even my most elaborate, artful knives are still knives first and foremost—and they are fully usable. On the other hand, I put just as much care and effort into my “cheapest” and most minimal designs as I do into the most expensive ones. That’s just part of my nature—I can’t bring myself to „cut corners“ on a knife just because it has a smaller budget. In fact, I often end up going overboard and doing extra work, simply because it feels like the knife deserves it.

I really enjoy making unusual, original knives with a “soul,” and whenever the budget allows, I devote a lot of time to the small details. I love both wild, artsy “crazy” pieces and historically inspired works from different cultures and eras. Often these elements blend together, and the result tends to be more of a fantasy/art/historical fusion.

Sticking to an exact template and making a flawless replica of a historical piece would certainly be tempting and fun, but in the long run I’d probably lose interest. I need to immerse myself in the work and let it carry me along.

It is deeply fulfilling for me to create “artifacts” from distant times, infused with their own kind of “magic”—mythopoetic pieces from the Viking age, fantasy worlds, or the era of the Wild West. I also enjoy working with more dynamic shaping of handles and blades, with various fullers and interesting details, intricately sculpted guards, and bone or antler handles with complex engravings.

With these historically inspired works, I often draw from original pieces and styles once used in different cultures. But it’s always more about inspiration than an attempt to follow an exact model.

And even if the result may sometimes feel close to the originals in certain aspects, it is almost always my own interpretation, where I let my imagination and creativity run free. So I kindly ask purists not to judge me too harshly.

On the other hand, I also enjoy making knives in a simple, rustic style. Pieces the owner won’t be afraid to use. But note that I understand the word “rustic” primarily as an aesthetic quality, not as a quick-and-dirty shortcut—i.e., not “the more hammer marks, the more ‘rustic.’” Even my most “forged-looking” knives always have proper fit and finish, to the same standard as my most luxurious pieces. Just perhaps in a simpler damascus or with fewer decorative details.

When I have enough time, calm conditions, and ideally a free hand to create, that’s when, in my opinion, the best work comes to life—the knives with a story. On the other hand, if a design doesn’t sit right with me from the start, or if someone pushes too hard for certain elements or materials, I know from experience that I just can’t swallow it and simply won’t accept some things. I wouldn’t be able to finish them in a way that I’d be satisfied with, and in the end the work wouldn’t be good.

If, after reading all this, you feel like you simply must have a carbon damascus knife—whether a simpler piece or something highly elaborate—and you’re patient as well as open to suggestions and my creative approach, don’t hesitate to reach out. I’ll be glad to plan a nice project with you for the future. Just keep in mind that the waiting time for my knives is usually quite long. You can find more about this in the “Orders” section

Conclusion & Contact

If you have any questions or are interested in placing an order, don’t hesitate to send me a message or call. I’ll gladly go over everything with you, explain the options, and help you choose—no obligation, in a straightforward way. Whether you’re after a “workhorse” knife with a soul or a special collector’s piece, let me know and I’ll promptly tell you what’s possible, the estimated availability, and an approximate price. In the “Orders” section you can read more about pricing and lead times.

Thanks—and if you like my work, feel free to follow me on social media. I’ll be happy to stay in touch. 🙂